Prefer Systemd Timers Over Cron¶

Systemd administrators often find themselves needing to run services on their bare-metal machines. Services can be broken down into roughly two broad categories:

- Long-running services that are started once and will run for the lifetime of the machine.

- Short-running services that are started at least once and will run for a short amount of time.

Long-running services comprise of the majority of the services in use by Linux. One of the challenging aspects of long-running services in a production environment is the dual question of monitoring and reliability:

- How do you know if your service is running?

- How will you be alerted if your service dies?

- How do you handle automatic retries should the service die?

- How do you enable automatic start-up of your services when a machine boots, and how do you make them start up in the right order?

containers are great too

This post only looks at non-virtualized, non-containerized services. Many excellent solutions exist if you have a container management system like Kubernetes or any of the cloud-hosted systems like Amazon ECS.

Running short-lived services as a cron job¶

The default suggestion is to create a cron job. cron is a simple utility in Linux for running commands periodically as defined in a cron table, or crontab for short.

0 16 * * * /usr/bin/echo "hello world" # (1)!

0 12 * * 6 /usr/bin/curl https://www.google.com >/tmp/google_html.txt &2>/dev/null # (2)!

- This line specifies that the command should run at 16:00 every day of the month, on every month of the year, and on every day of the week.

- This line specifies that the command should run at 12:00 every day of the month, on every month of the year, but only on Saturdays. Note that the day-of-the-week specifier is AND-ed with the day-of-the-month specifier.

Benefits¶

- This requires minimal setup. Most linux distributions pre-install crond which allows you to define user-level crontabs with no prior configuration.

- It's easy to use. The line in the crontab is exactly what will be run. There is no templating system in use, so you generally won't have to worry about escaping special values.

Drawbacks¶

- There is no easy way to determine if the command completed successfully.

- There is no easy way to know if the command was run at all.

- Log management is a pain. Your only solution for logging stdout/stderr is to redirect it to a file, however you'd also need to ensure you rotate the logs to ensure the log's size is bounded.

- There is no way to specify if you want the command to be retried, should it fail.

- It's not easy to get a quick glance of how long each line has until its next execution. Reasoning about all of your cron lines as a whole is basically impossible.

These drawbacks make a crontab wholly unsuitable for a reliable production system.

Running short-lived services as a systemd timer¶

Let's take for example a service that needs to periodically scrape a user's home directory and send the total list of files to an external logging backend.

We can use ncdu to give us a nice JSON representation of the file tree with each directory element's size. We pipe the JSON output to jq to format it into a more readable state.

ubuntu@lclipp:~/systemd_blog$ ncdu . -o - | jq .

[

1,

0,

{

"progname": "ncdu",

"progver": "1.11",

"timestamp": 1687459411

},

[

{

"name": "/home/ubuntu/systemd_blog",

"asize": 4096,

"dsize": 4096,

"dev": 2049,

"ino": 259370

},

{

"name": "file2.dat",

"asize": 2097152,

"dsize": 2097152,

"ino": 259372

},

[

{

"name": "subdir",

"asize": 4096,

"dsize": 4096,

"ino": 259382

},

{

"name": "file3.dat",

"asize": 1048576,

"dsize": 1048576,

"ino": 259383

}

],

{

"name": "file1.dat",

"asize": 1048576,

"dsize": 1048576,

"ino": 259371

}

]

]

Create the .service file¶

We can write a user-level systemd unit file by placing it into the proper folder.

ubuntu@lclipp:~/systemd_blog$ mkdir -p ~/.config/systemd/user/

ubuntu@lclipp:~$ vim ~/.config/systemd/user/ncdu.service

[Unit]

Description=ncdu scraping of user homedir

[Service]

ExecStart=/usr/bin/bash -c "ncdu ~/systemd_blog -o - | jq ."

WorkingDirectory=/home/ubuntu

If everything was done correctly, you can now view the service

ubuntu@lclipp:~$ systemctl --user status ncdu.service

○ ncdu.service - ncdu scraping of user homedir

Loaded: loaded (/home/ubuntu/.config/systemd/user/ncdu.service; static)

Active: inactive (dead)

ubuntu@lclipp:~$ systemctl --user status ncdu.service

○ ncdu.service - ncdu scraping of user homedir

Loaded: loaded (/home/ubuntu/.config/systemd/user/ncdu.service; static)

Active: inactive (dead)

Jun 22 18:16:05 lclipp bash[3592]: }

Jun 22 18:16:05 lclipp bash[3592]: ],

Jun 22 18:16:05 lclipp bash[3592]: {

Jun 22 18:16:05 lclipp bash[3592]: "name": "file1.dat",

Jun 22 18:16:05 lclipp bash[3592]: "asize": 1048576,

Jun 22 18:16:05 lclipp bash[3592]: "dsize": 1048576,

Jun 22 18:16:05 lclipp bash[3592]: "ino": 259371

Jun 22 18:16:05 lclipp bash[3592]: }

Jun 22 18:16:05 lclipp bash[3592]: ]

Jun 22 18:16:05 lclipp bash[3592]: ]

We can use the systemd journal to view the logs:

ubuntu@lclipp:~$ journalctl --user -u ncdu.service | tail -n 10

Jun 22 18:16:05 lclipp bash[3592]: }

Jun 22 18:16:05 lclipp bash[3592]: ],

Jun 22 18:16:05 lclipp bash[3592]: {

Jun 22 18:16:05 lclipp bash[3592]: "name": "file1.dat",

Jun 22 18:16:05 lclipp bash[3592]: "asize": 1048576,

Jun 22 18:16:05 lclipp bash[3592]: "dsize": 1048576,

Jun 22 18:16:05 lclipp bash[3592]: "ino": 259371

Jun 22 18:16:05 lclipp bash[3592]: }

Jun 22 18:16:05 lclipp bash[3592]: ]

Jun 22 18:16:05 lclipp bash[3592]: ]

Create the .timer file¶

The timer file can be made in a similar way.

[Unit]

Description=Periodically run the ncdu service

Requires=ncdu.service

[Timer]

Unit=ncdu.service

OnCalendar=*-*-* *:*:00

[Install]

WantedBy=timers.target

Now we have to activate it

ubuntu@lclipp:~$ vim ~/.config/systemd/user/ncdu.timer

ubuntu@lclipp:~$ systemctl --user enable ncdu.timer

Created symlink /home/ubuntu/.config/systemd/user/timers.target.wants/ncdu.timer → /home/ubuntu/.config/systemd/user/ncdu.timer.

ubuntu@lclipp:~$ systemctl --user start ncdu.timer

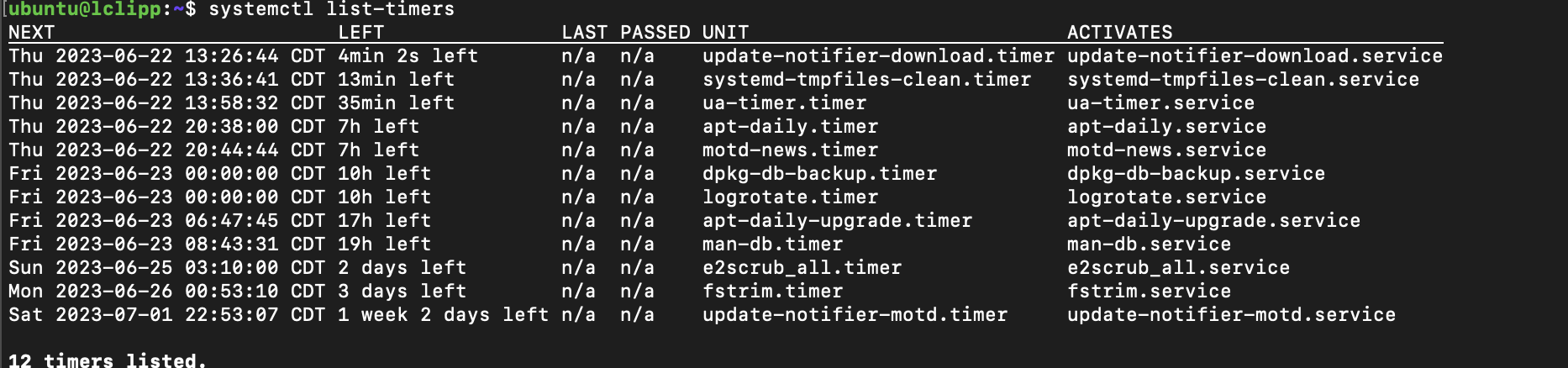

ubuntu@lclipp:~$ systemctl --user list-timers

NEXT LEFT LAST PASSED UNIT ACTIVATES

Thu 2023-06-22 18:21:00 CDT 30s left n/a n/a ncdu.timer ncdu.service

1 timers listed.

Pass --all to see loaded but inactive timers, too.

Benefits¶

- Tighter visibility into service states.

- Service states are queryable by external services

- Expressive configuration options for service restart behavior.

- Expressive configuration options for determining what an "active" state actually means

- Unit templating syntax

- Support for forwarding journal logs to external logging mechanisms

- Built-in and configurable log retention policies

Because the states are queryable, you can do cool things like graph the states in a state timeline in grafana.

This chart was created by using the systemd_unit telegraf plugin which forwards the state information to an InfluxDB database, which grafana then queries for the visualization.

Drawbacks¶

- The configuration is more complicated

- The templating system is somewhat clunky because of the escaping you have to do in

ExecStart=. You are also restricted to only a single template variable. - timer units are incapable of sending variable data to the service's template variable. There are many cases in my job where I would like to have a separate systemd unit for each calendar date. For example, we might want something like this: but this is actually exceedingly difficult to do, due to the variable nature of the date string. The timers which would instantiate these services can only send a static string, not a variable.