Analyzing Go Heap Escapes¶

In this blog post, we discover how you can analyze what variables the Go compiler decides should escape to the heap, a common source of performance problems in Golang. We'll also show how you can configure the gopls language server in VSCode to give you a Codelens view into your escaped variables.

What is a Heap?¶

The working memory of most modern programs is divided into two main categories: the stack, which contains short-lived memory whose lifetime is intrinsically tied to the lifecycle of the stack of function calls, and the heap, which contains long-lived memory whose lifetime transcends your stack of function calls. The Go compiler has to make a decision on where a particular piece of data should reside, by running what's called an Escape Analysis Algorithm. If the analysis decides that an object can be referenced outside of the lexical scope which created it, it will allocate it on the heap.

Why is the Heap a Problem?¶

Garbage-collected languages like Go have to periodically sweep the tree of object references allocated on the heep to determine if the reference is reachable (meaning some part of the code might still potentially access it) or if the reference is orphaned. If it's orphaned, it's impossible for the code to ever use it, so we should free that memory. This process is highly memory-intensive and slows execution of the application. The garbage collector is a necessary evil due to the fact that Go does not require the programmer to manually free memory.

Configuring VSCode for GC Heap Escape Highlighting¶

You can configure VSCode to highlight cases of heap escapes:

The VSCode plugin for Go provides integrations with its gopls language server. The language server is simply a subprocess that VSCode calls and creates a UNIX pipe through which queries and responses to the server can be sent (you can also run gopls as a TCP server listening to a local port). gopls can be configured in your VSCode workspace settings to highlight instances of heap escape in your code.

If VSCode has not yet created a workspace for your project, open File/Save Workspace As, and save a workspace file in the root of your project. The configuration I used for this blog is this:

{

"folders": [

{

"path": "."

}

],

"settings": {

"go.enableCodeLens": {

"runtest": true # (1)!

},

"gopls": {

"ui.codelenses": { # (2)!

"generate": true,

"gc_details": true # (3)!

},

"ui.diagnostic.annotations": {

"escape": true # (4)!

},

"ui.semanticTokens": true

},

}

}

- This is not relevant to GC highlighting, but is useful for Codelenses for unit tests

- These are the parameters you need to enable general GC annotations

- This enables a Codelens option for toggling the GC decisions on/off

- This actually enables the escape annotations

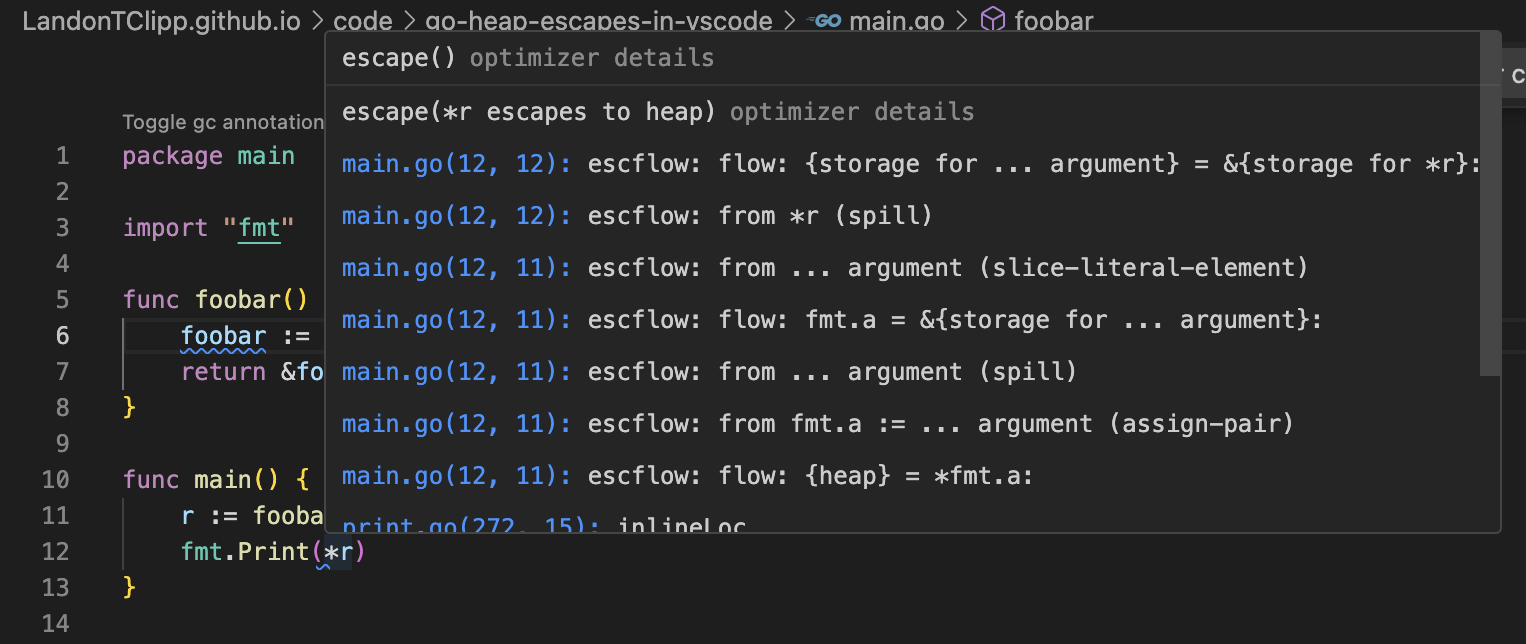

After doing this, hovering your mouse over the highlights show the results of the escape analysis:

Situations which cause escapes¶

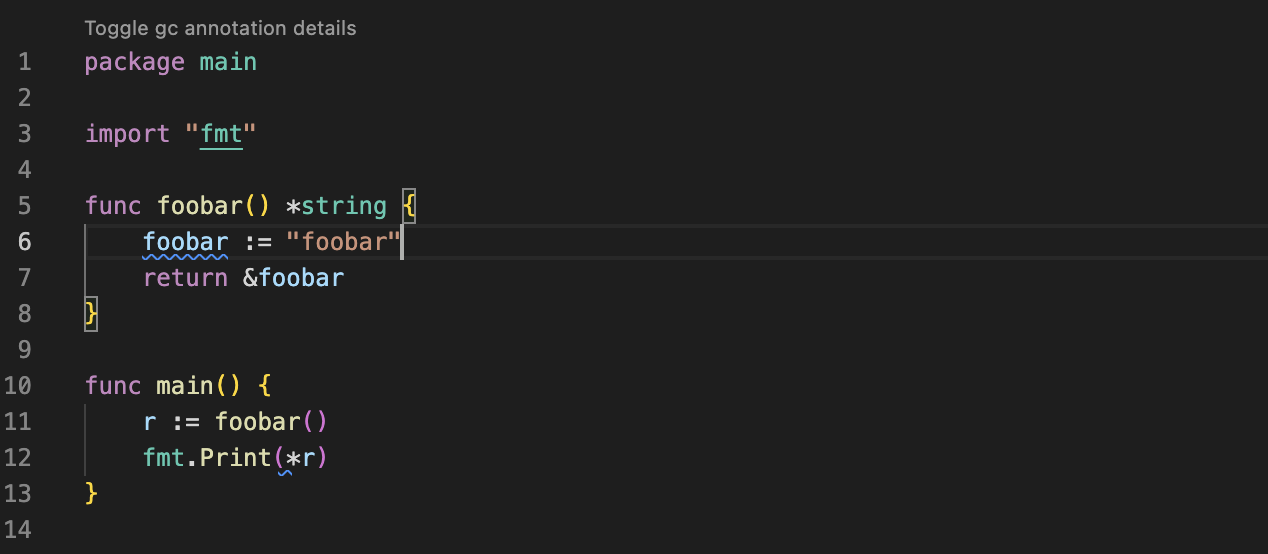

Returning pointers to local objects¶

We can run standard go CLI tools to generate an analysis of our code. The highlighted lines will represent lines where escapes were found.

| Go | |

|---|---|

We call go build with the following garbage collector flags to tell it to generate debug info on various decisions it's made, and output the results into a directory called out:

$ go build -gcflags='-m=3' . |& grep escape

# go-heap-escapes

./main.go:6:2: foobar escapes to heap:

./main.go:12:12: *r escapes to heap:

./main.go:12:11: ... argument does not escape

./main.go:12:12: *r escapes to heap

You can also specify go build -gcflags='-m=3 -json=file://out' . to have it print the results to a number of json files.

Looking closer at the output, we see these messages:

./main.go:6:2: foobar escapes to heap:

./main.go:6:2: flow: ~r0 = &foobar:

./main.go:6:2: from &foobar (address-of) at ./main.go:7:9

./main.go:6:2: from return &foobar (return) at ./main.go:7:2

./main.go:6:2: moved to heap: foobar

This is telling us very clearly that foobar escapes to heap. It's pretty obvious why, let's take a closer look.

This function instantiates a string named foobar that has the value "foobar". We return a pointer to foobar which then means that the string initially allocated on the stack of func foobar() *string can now be referenced by functions outside of this lexical scope. So the variable can't remain on the stack; it has to escape to the heap.

The message even tells us exactly why it escapes and what sequences of events had to happen for it to escape. By following the escape flow messages, we can see the two necessary events were:

./main.go:6:2: from &foobar (address-of) at ./main.go:7:9

./main.go:6:2: from return &foobar (return) at ./main.go:7:2

It escapes because we:

- We took the address of

foobar - We returned that address

Use of reflection¶

We also see that there's another escape on line 12 in the fmt.Print.

./main.go:12:12: *r escapes to heap:

./main.go:12:12: flow: {storage for ... argument} = &{storage for *r}:

./main.go:12:12: from *r (spill) at ./main.go:12:12

./main.go:12:12: from ... argument (slice-literal-element) at ./main.go:12:11

./main.go:12:12: flow: fmt.a = &{storage for ... argument}:

./main.go:12:12: from ... argument (spill) at ./main.go:12:11

./main.go:12:12: from fmt.a := ... argument (assign-pair) at ./main.go:12:11

./main.go:12:12: flow: {heap} = *fmt.a:

./main.go:12:12: from fmt.Fprint(os.Stdout, fmt.a...) (call parameter) at ./main.go:12:11

./main.go:12:11: ... argument does not escape

./main.go:12:12: *r escapes to heap

What's going on here? Let's take a closer look at what fmt.Printis doing. Under the hood, it calls this function. We can port the relevant parts of this logic into our editor. We copy the lines that do all of the reflection but leave out the complicated format parameter logic that isn't needed in our toy example.

After some investigation, I found that simply removing the .Kind() call results in no escapes happening:

- We do this

reflect.TypeOfcheck to ensure thatreflect.TypeOfis actually used. Our goal is to keep thereflect.TypeOfcall but not the.Kind()

As you can see, the .Kind() call itself seems to be the determining factor on whether or not it escapes to the heap. The exact reason is a bit unclear, but if you look at the source code of the reflect package, you see lots of examples of the usage of unsafe.Pointer which is probably defeating the escape analysis by obscuring the type that the pointer points to, which consequently limits its ability to inspect which lexical scopes have references to the type. Someone who is more familiar with the internals of reflect should chime in and let me know if this is an accurate assessment.

Use of interfaces¶

This is not a new discovery. It has been known about for a long time by multiple different bloggers. It turns out that the Go compiler is incapable of knowing at compile-time whether the underlying type in an interface could cause the reference to escape the stack. From the perspective of the function taking an interface as an argument, this knowledge is difficult to know at compile time. 1

We can see this is true even in the simple case where the argument is a bare interface:

| Go | |

|---|---|

./main.go:9:20: ([]byte)(s) escapes to heap:

./main.go:9:20: flow: asBytes = &{storage for ([]byte)(s)}:

./main.go:9:20: from ([]byte)(s) (spill) at ./main.go:9:20

./main.go:9:20: from asBytes := ([]byte)(s) (assign) at ./main.go:9:10

./main.go:9:20: flow: {heap} = asBytes:

./main.go:9:20: from w.Write(asBytes) (call parameter) at ./main.go:10:9

./main.go:8:12: parameter w leaks to {heap} with derefs=0:

./main.go:8:12: flow: {heap} = w:

./main.go:8:12: from w.Write(asBytes) (call parameter) at ./main.go:10:9

./main.go:8:12: leaking param: w

./main.go:8:25: s does not escape

./main.go:9:20: ([]byte)(s) escapes to heap

The compiler claims that []byte(s) escapes because it's being passed to w.Write, which is a method on an interface. On the contrary, if we change w to *bytes.Buffer, the compiler no longer claims an escape:

| Go | |

|---|---|

Use of reference types on interface methods¶

It's not enough to say that interfaces cause escapes, as we'll find below. Interfaces cause escapes only if we send reference types to one of its methods. The astute reader may have noticed that in our previous examples, the types we were sending to our interfaces were all reference types. What if we send value types?

| Go | |

|---|---|

And going back to a reference type, we can see yet again that simply changing the argument to a reference type causes it to escape.

| Go | |

|---|---|

What if we use a reference type on a non-interface value? Instead of print taking a Writer interface, we modify it to take a writer struct directly:

package main

type writer struct{}

func (w writer) Write(b []byte) (int, error) {

return 0, nil

}

func print(w writer) {

s := "foobar"

b := []byte(s)

w.Write(b)

}

func main() {

print(writer{})

}

Criteria for Escape¶

This repo provides a wonderful explanation of how escapes actually happen.

Criteria for Escapes

There is one requirement to be eligible for escaping to the heap:

- The variable must be a reference type, ex. channels, interfaces, maps, pointers, slices

- A value type stored in an interface value can also escape to the heap

If the above criteria is met, then a parameter will escape if it outlives its current stack frame. That usually happens when either:

- The variable is sent to a function that assigns the variable to a sink outside the stack frame

- Or the function where the variable is declared assigns it to a sink outside the stack frame

Interfaces are a special case of the reference type, because as stated before, the compiler at compile-time has no idea what the implementation of the interface looks like so it has to shortcut its analysis and assume that an escape will happen. The methods defined on other reference types, like *bytes.Buffer, can be statically inspected by the analyzer to determine escapes.

Criteria for Leaks¶

The linked repo above also explains to us what a leak is.

Criteria for Leaks

There are two requirements to be eligible for leaking:

- The variable must be a function parameter

- The variable must be a reference type, ex. channels, interfaces, maps, pointers, slices

Value types such as built-in numeric types, structs, and arrays are not elgible to be leaked. That does not mean they are never placed on the heap, it just means a parameter of int32 is not going to send you running for a mop anytime soon.

If the above criteria is met, then a parameter will leak if:

- The variable is returned from the same function and/or

- is assigned to a sink outside of the stack frame to which the variable belongs.

A leak can also happen without escaping. Consider the case where a value is allocated in frame 0, passed into frame 1 as a pointer, and frame 1 returns that pointer back to frame 0:

| Go | |

|---|---|

We can see it mentions fooString leaking, but nowhere does it say it escaped. This is because it knows that the string never escapes from main even though the pointer in foo() leaks its argument to the return value.

Conclusions¶

These experiments lead us to conclude a few main points:

- Usage of reflection involves unsafe pointers, which defeats the escape analysis and causes escapes.

- Some of the basic packages like

fmtheavily use reflection (and consequentlyunsafe.Pointer) to determine the types being passed to print functions and how to resolve them into the print format specifiers. - Reflection should not be used unless absolutely necessary. Leveraging type safety in go allows it to inspect your program to determine whether an object can truly remain on the stack, or if it must be on the heap.

- Go makes conservative assumptions. If there is any doubt whatsoever about whether something can escape, it assumes it can. The alternative would be a program that handles garbage data, and even segfaults, due to unclear reasons.

- Because it's difficult to know at compile time whether the underlying type of an interface could cause a value to escape, the escape analyzer has to assume it's possible. Thus, any time a reference type is passed to an interface, it will escape.

- Using VSCode Codelens can help us catch cases of heap escapes and make us think critically about whether or not our abstractions are truly necessary.

Lifetime annotations¶

The grammar of Go does not provide hints to the compiler that lets us tell it what the lexical scope of a reference will be. Other languages like Rust provide lifetime annotations that allow us compile-time guarantees that a reference will be valid at runtime. These annotations allow you to tell the compiler which lifetime a reference is attached to. Take for example this theoreical Go code:

func yIfLongest<'a, 'b>(x &'a *string, y &'b *string) &'b *string {

if len(*y) > len(*x) {

return y

}

s := ""

return &s

}

This is some complicated syntax, but those familiar with Rust might understand what's going on. Otherwise, bear with me. func yIfLongest<'a, 'b> is telling us that there are two separate lifetimes in our function, 'a and 'b. We assign x to the 'a lifetime and y to the 'b lifetime, and claim that the return value's lifetime should be the same as y. If the compiler has this information and already knows that y should never escape the stack, then it by extension knows that the return value also cannot escape the stack. Consider the alternative Go code without these annotations:

package main

import (

"os"

)

func yIfLongest(x, y *string) *string {

if len(*y) > len(*x) {

return y

}

s := ""

return &s

}

func main() {

x := "ab"

y := "abcde"

result := yIfLongest(&x, &y)

os.Setenv("Y", *result) //(1)!

}

./main.go:11:2: s escapes to heap:

./main.go:11:2: flow: ~r0 = &s:

./main.go:11:2: from &s (address-of) at ./main.go:12:9

./main.go:11:2: from return &s (return) at ./main.go:12:2

./main.go:7:20: parameter y leaks to ~r0 with derefs=0:

./main.go:7:20: flow: ~r0 = y:

./main.go:7:20: from return y (return) at ./main.go:9:3

./main.go:7:17: x does not escape

./main.go:7:20: leaking param: y to result ~r0 level=0

./main.go:11:2: moved to heap: s

- I'm not using

fmt.Printhere because we've already shown that it causes escapes. Setting an environment variable is an easy task that doesn't require the use ofreflect.

The escape analyzer is showing us that while the y argument does indeed leak out of the function because we're returning it in some logical flows, it never escapes because it inspects main() and sees there's no opportunity for it to escape. However, it does decide that s must escape because we're returning the address of a local variable.

While go perfectly allows returning the address of local variables (due to the escape analysis and its garbage collector), a similar activity in Rust will greet you with an angry compiler2:

$ cargo run

Compiling chapter10 v0.1.0 (file:///projects/chapter10)

error[E0515]: cannot return reference to local variable `result`

--> src/main.rs:11:5

|

11 | result.as_str()

| ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^ returns a reference to data owned by the current function

For more information about this error, try `rustc --explain E0515`.

error: could not compile `chapter10` due to previous error

This is because Rust does not automatically allocate memory, while Go does. This is a tradeoff that Go has made for the benefit of a simpler developer experience. If Go were to adopt a lifetime annotation syntax, theoretically it could allow the compiler to make more informed decisions about whether or not a local variable needs to escape to the heap. If we're telling it that its lifetime is equal to y, then the compiler will decide based off of what y's lifetime is doing. This could provide much more intelligence around the other more confusing behavior surrounding interfaces (and maybe even reflection). It could also enable the compiler to disallow any operations that would violate the lifetime we specified. This would reduce the flexibility granted by the garbage collector, but we could avoid its cost.

Parting thoughts¶

I have seen lots of people grow upset about how even simple instructions like fmt.Print cause heap allocations. If you dive into the theoretical basis of Go and what it's trying to achieve, you begin to realize just how complicated it is to get reference lifetime decisions right if you don't have the proper syntax. Go's entire mantra is to make the grammar as simple and approachable as possible, which is likely why this sytax hasn't manifested. This has real benefits when it comes to developer productivity as instead of agonizing over the details of memory management, you simply write the code you want and the memory is handled for you.

Go trades some amount of memory and CPU efficiency for the goal of developer friendliness. Its code is easy to read because debates about where memory should reside are deferred to the compiler, thus the syntax becomes minimalistic and free of memory-managing instructions. It is no doubt that languages like C, C++, or Rust will always beat Go in terms of latency, memory efficiency, and CPU efficiency. But the workflows Go is geared towards (cloud and systems-of-systems based environments) are heavily bound by external IO anyway, which makes most of these complaints irrelevant. There are many tools at your disposal, and you must always pick the right one for the job.

-

It might theoretically be possible to ascertain this knowledge by inspecting the entirety of a program and seeing if any type that is boxed into an interface might cause the reference to escape. To my knowledge, the escape analyzer does not do this, and it's unknown whether doing such a whole-program analysis is even tractable. ↩

-

These examples are copied directly from Rust's documentation ↩